A mother storms toward her son. Provoked by his belligerent denial of her motherhood, she delivers a resounding slap, leaving a vivid red mark across his back.

As soon as this suspenseful sequence – positioned just before the midpoint of The Fabelmans (2022) – dissolved, the Spielberg film that surfaced in my mind was none other than Schindler’s List. More specifically, it recalled the infamous ‘gas chamber’ sequence from Spielberg’s 1993 Holocaust drama. Long embroiled in the contentious polemic between ‘Saint Paul’ Jean-Luc Godard and ‘Moses’ Claude Lanzmann over the ethics of representing concentration camps on film, Spielberg’s sequence became a flashpoint in the dispute over whether the gas chamber – widely regarded as the apogee of historical unrepresentability – can ever be mobilized as a site of cinematic suspense. It goes without saying that Spielberg was excoriated by both Godard and Lanzmann (and here we catch a glimpse of a deeper philosophical tension: the postwar European intellectual’s unrelenting, and perhaps overdetermined, fidelity to the Holocaust as the absolute ethical limit of representation. This discussion, while crucial, must be deferred as it lies beyond the present scope). Yet, in the wake of The Fabelmans, I find myself increasingly convinced that Spielberg was never even able to begin to grasp the thrust of Godard and Lanzmann’s objections. This is because, for Spielberg, cinema is violence and suspense.

Try to recall a single Spielberg film entirely free of physical violence. Even in his ostensibly non-violent ‘drama’ genres – Always (1989), The Terminal (2004), and Lincoln (2012) – we invariably encounter moments of physical or emotional tension acute enough to make us wince. There was a time when some critics naively claimed to have discovered “Spielberg the [old-fashioned] humanist” in the discreetly veiled, off-screen execution scene of War Horse (2011). Yet such appeals to humanism remain plausible only if one willfully overlooks the ferocious battle sequences that open the very same film (Properly viewed, War Horse stands in formal counterpoint to War of the Worlds (2005): a successful Spielbergian experiment in distilling, condensing, and simplifying violence as much as possible).

“How does one depict violence in an original way?” “How can suspense be delivered afresh?” These are not merely incidental curiosities but repetitive, cathectic obsessions that form a central pillar of Spielberg’s filmography. At the very root of this sustained concern for violence and suspense lies the intuition that montage – the collision and intertwining of irreducibly heterogenous events A and B – is inherently violent, yet mysteriously beautiful (recall, for instance, the telepathic moment in E.T.). In this light, The Fabelmans emerges as a keystone film in Spielberg’s oeuvre: not only does Spielberg reflectively unravel his own fixations with violence and suspense, but he also performatively demonstrates their inevitability – indeed, their necessity – as properties intrinsic to cinema itself.

Here, the meaning of “violence” and “suspense” extends beyond the purely physical. There is the violence that the camera inflicts by pointing, framing, and shooting its subject, embodied in Logan’s quiet distress at watching himself on the big screen. There is a perverse hunger for suspense that is initially attracted to, but ultimately causes and deepens, catastrophic emotional rifts, reflected specularly in Sammy’s compulsive fantasy of rolling the camera even in the very moment his parents announce their divorce. There is also the unsettling power of film to bring the past vividly back to life, violently dislocating and alienating the present – as when the Fabelman family simulate domestic harmony in a silent home movie filmed just after their relocation. In The Fabelmans, Spielberg patiently and meticulously charts how such filmic acts – shooting, editing, projecting, watching – unfold and intervene in the lives of those they capture. It is not unreasonable to view The Fablemans as Spielberg’s own research note: an experiment in cinematic violence conducted within the semi-autobiographical frame of his own youth.

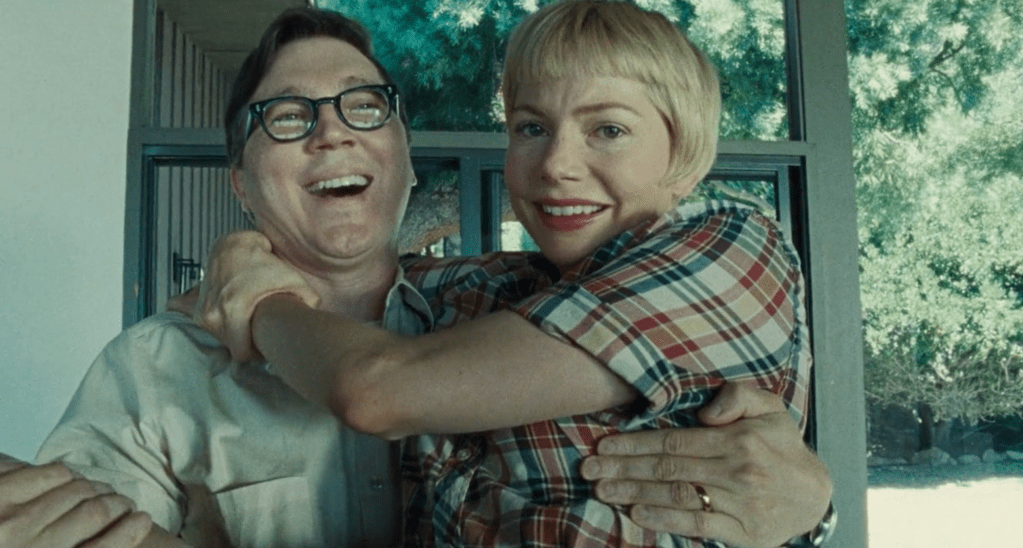

But Spielberg is no cynic content simply to declare the violence of cinema. When Sammy’s sister Reggie rebukes him for his apparent emotional detachment – watching him resume editing immediately after their parents’ separation – she nonetheless sits beside him and silently rests her head on his shoulder when he asks her to watch the cut with him. Similarly, while Sammy himself cannot bear to watch the entirety of his graduation film, the comedic commotion and emotional chaos that ensue pull him right back into filmmaking (“Unless I make a movie about it”). That is to say: films are the very things that shatter and estrange life (“this business… it’ll rip you apart”), yet they are also the very stuff that enable us to live on amid the wreckage. Is this not precisely what Uncle Boris’s grand monologue tries to get at, beneath its carnival absurdity? Films are incredibly mercurial and paradoxical stuff, demanding everything and yet giving something essential in return, at once brutalizing and redeeming, wounding and stitching. In The Fabelmans Spielberg does not merely confess this aporia at the heart of cinema. He embraces it without reserve.

But there is one further dimension worth considering. What proves mercurial and paradoxical is not only cinema itself, but also Spielberg – the filmmaker who affirms cinema with such force. The Fabelmans stands as a mournful testament to a bygone era: a time when films were literally composed of film, when cinema still held the promise of shared experience, when audiences believed they were inhabiting the same emotional world simply by watching the same projected image, and when our imagination was sensitive enough to be stirred by the simple cut – the crossing of one image with another. Yet one of the central figures responsible for bringing that era to a close is none other than Spielberg himself. He is the director who introduced cutting-edge CGI in Jurassic Park, forever altering the visual language of mainstream cinema and inaugurating a new visual regime; the architect of a new cinematic mode of production in which films became closely integrated with television, video games, and merchandise – laying the foundation for the franchise economy. In view of this, The Fabelmans comes to assume an ambivalent, almost uncanny status. This is not to accuse Spielberg of bad faith or hypocrisy, but to recognize the depth of the aporia he himself inhabits. At this point, it is difficult not to bring to mind the theory of “the two Spielbergs” that many critics have long spoken of since the 1990s. We must recall that Sammy possesses two edited versions of his camping trip film, both composed with equal care. Across his career, Spielberg has repeatedly produced films animated by two contradictory forces, struggling within the same filmic body. At the risk of being repetitive, The Fabelmans is a film enmeshed in intense paradoxes, both internal and external.